Blog

Category: Web Design

Mastering the Art of Project Managing a Website Redesign: Tips and Strategies for Success

9 Website Redesign Mistakes that Destroy SEO

Website Redesign Timeline – How Long It Should Take

How Often Should You Redesign Your Website? – A 2024 Guide

40+ Website Key Performance Indicators to Measure Your Websites Performance

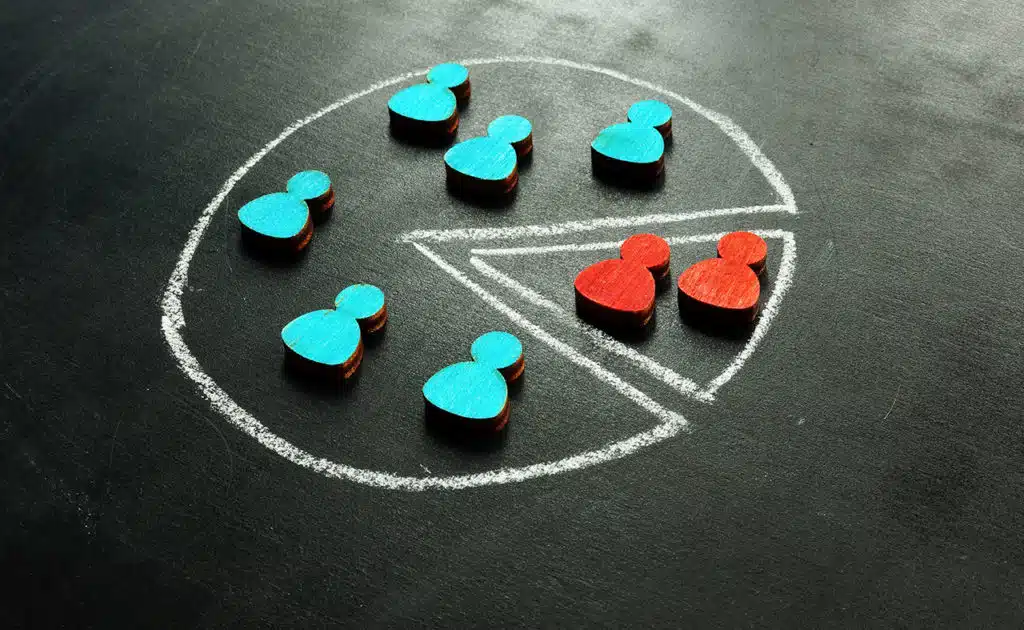

How to Define and Segment Your Websites Target Audience

How to: Get More Leads From Your Website (10 ways)